Auschwitz-Birkenau - Visitors' Manual Guide - text written by Tomasz Cebulski for Humanity in Action for their publication volume REFLECTIONS ON THE HOLOCAUST published by Humanity in Action in New York 2011.

Double life of Gitta - article written by Tomasz Cebulski on the basis of one of the Jewish genealogy research projects conducted in 2010 in Biała Podlaska.

Memory of the Holocaust and the shaping of Jewish Identity in Israel - paper presented by Tomasz Cebulski on the "Legacy of the Holocaust" conference, organized by the University of Northern Iowa and the Jagiellonian University in Cracow, May 2007.

Discovering the History of a Lost World by Tomasz Cebulski

Who Were Those Heroes ?

Stories are complicated. They can take us to unexpected places and leave us with more questions than answers. Endings often surprise us. What we thought might be the end of a story might actually be something else-the middle, maybe, or a point along some continuum. My family's story has many unknowns. My parents, no longer living, were Holocaust survivors from Miechow, Poland. I am looking for information about the people who helped save my mother and grandmother during the war.

When my mother was alive, I did not ask her many questions about her experiences during the Holocaust. To her the past was something she tried to leave behind. To me her life as a Jew from Miechow, Poland has been inextricably tied to mine. I am hoping that someone reading this might recognize the people in the photographs below and be able to answer a question that I cannot answer on my own: Who were the heroes who helped save my mother and grandmother?

Photograph taken in Krakow in 1943

Over and over, for years, hoping to see some clue I had previously overlooked, I have carefully studied this 1943 photograph taken in Krakow, Poland. The dark-haired woman on the far left is my mother. My grandmother sits on the opposite end of the sofa. On my mother's left, sitting on the arm of the sofa, is a man with rounded glasses. His face is familiar because he appears in other photographs in our photo album. I believe his name is Werzel Waschak. I don't recognize the two women seated between my mother and grandmother. I have so many questions, but there is one thing that I am fairly certain of. I believe that this man and these women saved my mother's and my grandmother's lives during the Holocaust.

My knowledge of my family's experiences during the war is spotty. I know that when the war broke out, my mother was fourteen and by the time she was seventeen, she was a prisoner at Plaszow concentration camp. I know that my mother survived because she and my grandmother were able to obtain false papers, "Aryan papers."

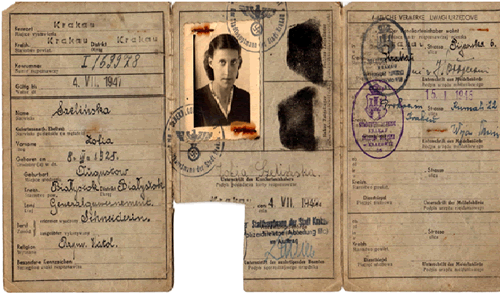

The Aryan Papers of Manya Gerszonowicz, 1942

My mother's Aryan papers identified her as Sofia Grelinska and her religion as Roman Catholic. Her given name was Manya Gerszonowicz. During the war, I believe she worked as a seamstress in Krakow returning at night to the home of the Polish family who hid her.

My Uncle Peter, my mother's older brother, wrote an unpublished autobiography that provides somer clues. He writes, "We met a man by the name of Werzel Waschak from Chemnitz, Germany. He was employed as a construction engineer in Krakow. We asked him for help and he agreed to try. He [was] anti Nazi, sympathetic to the Jewish people. He wanted to help. He was successful and found a place with a family for my mother and the older one of my sisters" (4). I had heard my parents talk about Werzel Waschak but I gleaned few details about his life. Werzel Waschak, in my mind, has always been a mystery.

Werzel Waschak

When it comes to stories about the war, there is no shortage of stories of anti Semitism. My relatives had plenty of them, stories about priests who hated Jewish children, neighbors who, for a pound of sugar, would turn in a Jewish friend. But there were other stories about people who took great risks, most with little money or food, all with families of their own.

I am a generation removed from the Holocaust, having grown up on a separate continent, never having lived through the unbearable pain that war brings. My grandmother and parents, my Uncle Peter and Aunt Genia have all passed away, but in my mind this story continues. It has been over seventy years since my mother and grandmother escaped a concentration camp in Krakow. It has been over seventy years since they were taken in by people who took a tremendous risk to save them.

The Wedding of David and Manya Jagoda, Munchberg, Germany 1946

I have often tried to imagine how these individuals came to the decision to help, how they decided the risks were worth taking. I have often tried to imagine where their courage came from, where they found the conviction to do the right thing in the shadow of so much hatred and danger.

To the families of those who saved my mother and grandmother, I am eternally grateful. I want to let you know that my mother immigrated to the United States, to St. Paul, Minnesota with my father. My parents had three children (a boy and two girls) five grandchildren (four of them married, one still in high school), and three great grandchildren.

If anyone reading this article recognizes any of the individuals in the photographs, I would be most grateful to hear from you. Please email me at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. To say thank you, I realize, may seem woefully inadequate in light of the tremendous risks involved, but I would like to say it anyway. Thank you, from the bottom of my heart.

Sincerely,

Liza Allen

POLISH VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE:

Suzy Hagstrom is the author of Sara's Children; The Destruction of Chmielnik, which records the remarkable survival of five siblings in Nazi Germany's death camps.

The San Diego journalist accompanied Speiser and Greenspun on their trip to Poland and Germany.

Helen Garfinkel Greenspun, a Jewish Holocaust survivor, has returned to her hometown of Chmielnik, Poland, only twice since World War II.

During her first visit in 1992, the Orlando, Florida, resident found the Jewish cemetery in ruins and its broken tombstones paving Chmielnik's sidewalks. Spray-painted swastikas defaced the town's historic synagogue, and plywood covered the entrances and windows. Some of Greenspun's former neighbors harassed her taxi driver demanding to know why he would dare bring Jews back to Chmielnik.

During her second visit 16 years later -- just this past June -- Greenspun found the town's Jewish cemetery partially restored and the synagogue in early stages of renovation. Chmielnik Mayor Jaroslaw Zatorski kissed Greenspun's hand to welcome her at several ceremonies honoring five Holocaust survivors and their families.

"I must be dreaming," Greenspun said countless times while traveling from Orlando, Florida, to Poland and Germany with her daughter Rita Renshaw, four grandsons and niece Arlene Garfinkel of Detroit, Michigan. Greenspun expected hostility yet she was determined to leave her family a legacy of her happy childhood as well as her traumatic World War II experience.

Only after buying airline tickets did Greenspun learn that her trip to Chmielnik would coincide with the town's Jewish festival. Then she didn't know what to expect. "A Jewish festival in Chmielnik? How can this be?" she asked repeatedly. "There are no Jews left in Chmielnik." Initially designed to examine Greenspun's past, the journey ultimately offered her a glimpse of the future.

In the same town square where German soldiers and snarling dogs had herded Greenspun, her siblings and other Jewish teenagers into trucks bound for slave labor camps, several thousand Chmielnik residents gathered for performances of klezmer music and Israeli folk dances. "This I can not believe," Greenspun said.

The contrast was equally jarring for Greenspun's four grandsons ranging in age from 14 to 29. "Wow, it's gone from 'Kill the Jews' to 'Jews go home' to a total celebration of Jewish culture," said Benjamin Turocy, the eldest. "The best part of this trip is seeing my Grandma so happy and so full of life," Turocy said while watching Greenspun mingle with people in the rynek, or town square. "That makes me happy. I know it means so much to her to see everything here."

With a current population of 4,200, Chmielnik had been home to an estimated 10,000 Jews and 2,000 non-Jews before World War II. The Nazis killed nearly all of the town's Jews, including Greenspun's parents, two younger siblings and other relatives, in Treblinka's gas chambers.

Chmielnik's annual Jewish festival -- held the third Sunday each June -- evolved from a 2002 weeklong commemoration of the town's 450th anniversary. City officials and teachers set aside one day to represent the town's former Jewish community.

"We thought to explain the Jewish culture was important," said Piotr Krawczyk, Chmielnik's fulltime historian. Documents and data culled from archives, libraries and government agencies show Jews formed the lion's share of the population during much of Chmielnik's history. "Chmielnik was a Jewish town. No question," said Krawczyk, 36.

Plans are underway to renovate the synagogue by 2012 and convert it to a museum of Jewish culture. Krawczyk acknowledged Chmielnik would like to attract tourists, especially Jews, but he stressed that developing the town’s economy is not the primary reason for restoring the synagogue. "The place (museum) about Holocaust you can find anywhere. We decided to show people something different -- the life before the war," Krawczyk said. "We decided to keep the memories for the new generations. How can we build the future if we forget the past?"

In 1992 no one was willing to help Greenspun look -- much less step -- inside the synagogue. This past June, Chmielnik city officials and festival volunteers ushered her to reserved chairs inside the synagogue for a special concert and art exhibit. The windows are gaping holes, scaffolding and dust abound, but observers can see the outline of lions supporting the crown of Torah. Seated on the ground floor where her father Kalman Garfinkel had worshipped, Greenspun turned to look at the balcony where her mother Sara Garfinkel had observed services.

Greenspun, 81; her brother Nathan Garfinkel; and three sisters -- Bela, Sonia and Regina -- were exploited as slave labor in Hasag ammunition factories in Kielce, Skarzysko-Kamienna and Czestochowa. Remarkably, the five siblings endured not only transfer to the German concentration camps of Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen and Dachau, but also grueling death marches in the war's final weeks.

The survival of so many family members is so rare it is recorded in a book, Sara's Children; The Destruction of Chmielnik. Like her siblings Sonia and Nathan, Helen speaks about her World War II experience at schools, civic organizations, places of worship and other public forums. Greenspun is a tireless volunteer for the Holocaust Memorial Resource & Education Center of Central Florida.

Sonia, 85, and Regina, 79, live in Detroit. The eldest sister, Bela, died in 1997 in Florida. Brother Nathan Garfinkel died in 2006 in Detroit. He traveled to Chmielnik in 1990 with his children. His daughter Arlene Garfinkel said that trip and this more recent journey with her Aunt Helen Greenspun were as different as night and day.

"This is amazing," Arlene said, noting that Poland's emergence into the 21st century is just as startling as the change in attitude. In 1990, "Chmielnik looked like a town that was never going to come back. The buildings were boarded up and closed." Both Arlene and Greenspun remember seeing women clad in long skirts and babushkas. Horse-drawn wagons outnumbered cars, they said. This past June the newly paved rynek bustled with stylishly dressed men and women. Small, fuel-efficient cars circled the plaza in search of parking spaces.

"I feel the festival is important for everyone at a lot of levels," said Joyce Ann of Chicago. Her father, Irwin Wygodny, 88, grew up on a farm near Chmielnik. During the war he lived through the work camps of Kielce, Waltzer and Annenberg. "The Polish people can meet Jewish people and know that we are real and not much different than them."

Most impressive, Ann said, was the integration of Jews and Poles during the festival. Representatives from local, regional and national government agencies -- including a minister sent by Poland's president -- attended various ceremonies during the three-day festival. Poland's president gave survivor Mijer Maly, 88, an award for fostering peace between Poland and Israel. Not only has Maly attended every festival since 2002, Krawczyk said, but also Maly visits Chmielnik at other times just to speak to schoolchildren. Maly has also arranged delegations of Chmielnik officials to meet school and government officials in Israel. "Mijer Maly is very special for us," Krawczyk said, "and he speaks Polish very well."

Krawczyk and other city officials also praised Joseph Kalish, a survivor from Haifa, Israel, for helping finance the partial restoration of Chmielnik's Jewish cemetery. An iron fence adorned with a menorah and stars of David now encloses half of the cemetery. Broken gravestones form a circular memorial inside the fence. Sadly, the other half of the cemetery lies under new housing. About 250 people gathered to observe Kalish cut the ribbon at the entrance.

About 50 girl and boy scouts made a chorus. They sang Shalom Alechem in Hebrew as well as Polish. Seeing the Israeli flag fly next to the Polish flag made her heart beat nearly out of her chest, said Greenspun, who was asked to speak at the dedication. "This I thought I would never see in my lifetime, and to hear the children singing. This I can not believe. I wonder how many little boys here are Jewish, and they don’t even know it?" Greenspun said and sobbed. She was referring to the descendants of Jewish babies and toddlers left with non-Jewish families during the war.

Her grandsons, daughter and niece often found themselves lagging behind as Greenspun raced ahead on cobblestone streets to find familiar places, most significantly the house where she grew up in Chmielnik and her maternal grandparents’ apartment building in Lodz. On reaching both destinations, Greenspun wept, overcome by memories of her grandmother waving in the window and her mother fetching water from the backyard well.

Likewise, on making the pilgrimage to Treblinka, where nearly 1 million Jews were annihilated in 17 months, Greenspun began running to find the stone marked Chmielnik. She had carefully tucked away some complimentary hotel matches in her purse to light a candle to honor her parents. Situated on a grassy field studded with human bone fragments as well as yellow and purple wildflowers, Treblinka’s memorial contains 17,000 boulders and rocks, representing the number of Jews gassed daily. More than 220 stones bear the names of villages, towns and cities whose Jews were transported to Treblinka.

“This trip was a lot more educational than I thought,” said Jake Renshaw, 15, a sophomore at Lyman High School. “In school, they present the Holocaust and the concentration camps in a nice little way, without all the violence. This way, going with my Grandma, it’s more direct, without the censorship.”

Rita Renshaw, Greenspun’s daughter, found the contrast between the ugly events of history and Poland’s natural beauty both ironic and surprising. “Growing up I only heard bad things –- about concentration camps and throwing babies into the fire. Poland always had a big ‘X’ on it,” Renshaw said, marveling at the gently rolling terrain and quaint wooden farmhouses featuring flower boxes, peaked roofs and dormers. “All those years Mom never told me about the beauty of the country or the scenery. But how could she after everything that happened during the war? My mother never thought of herself as Polish. She only thought of herself as Jewish.”

Greenspun acknowledged that her emotions conflicted constantly while planning the trip. On one hand she wanted to share her personal history by physically showing her family the places she had lived and survived. On the other, she dreaded being a tourist in nations that had perpetrated genocide. “I said I would never set foot in Germany again. I never would have gone to Germany if it hadn’t been for my children.”

Throughout the journey, Greenspun and her family discussed the controversies of Jewish heritage tourism in Europe and spending money where anti-Semitism had flourished so visibly less than 20 years ago. They also doubted whether the various Jewish festivals in Poland are completely altruistic. The spirit of Tikum Olem, or “repair the world,” was as much the result of donations from Israelis and the willingness of survivors such as Kalish to visit as from the sincerity, earnestness and outreach of Chmielnik officials.

“Grandma doesn’t want me to buy German cars or support German companies in any way,” Turocy said. But “I felt if we were going to have a true, full trip seeing the concentration camps and Poland, Germany was an essential part that we couldn’t miss.”

Consequently, one of the family’s final stops was the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial near Munich, where Helen and her three sisters were liberated in April 1945. Albert Knoll, the memorial’s historian and archivist, showed Greenspun and her family documents listing the Garfinkel sisters as prisoners. He also showed them photographs of nearby camps where the four sisters were imprisoned: Burgau, Turkheim and Allach.

Typical of many concentration camp sites, Dachau’s exhibits and memorials are contained in an area much smaller than the original camp. “Allach is the third-largest sub-camp of Dachau,” Knoll said, describing the factories where BMW exploited slave labor to make aircraft engines. “It (Allach) had more than 10,000 prisoners, and nothing more remains. There’s just one plaque in English and French in a parking lot.” The annual reunion of Dachau survivors is held the first Sunday after April 29, Knoll said, and that group grows smaller each year. “Families come from all over the world. It’s often the children and grandchildren of survivors who say, ‘Now let’s do a visit here.’”

Unlike Greenspun, many survivors are unable to describe their experience, Knoll said. On setting foot inside the Dachau’s memorial, Greenspun recognized the guard towers. On viewing photos of Turkheim’s cells for prisoners, Greenspun remembered that they were dirt caves. She was gratified to see so many people visiting the memorial, including school groups, busloads of tourists and German soldiers, who are required by law to visit concentration camp sites. “Take a look at how many kids are coming here,” Greenspun said. “I hear all languages here.”

Greenspun's youngest grandson, Chad Renshaw, 14, said that of everything he had seen in Poland and Germany related to his family, Chmielnik's cemetery had the most impact. "I can't believe people actually broke the gravestones and paved the road with them," Renshaw said. "I think it's good they fixed the cemetery so people can go visit family members and friends that were buried there."

Speech delivered at the opening of Paul Brown photography exhibition in Newcastel, January, 14th 2008.

Good afternoon,

My name is Tomasz Cebulski. I am a guide and a Holocaust researcher. Thanks to the invitation of the Newcastel City Council I came today from Cracow in Poland to have this chance and honor to say a few words about the work of my friend Paul Brown.

I will try to be brief as this is the evening of images and pictures more then the spoken word.

The images you can see are the results of Paul Brown's work in eastern Poland last year. After a successful visit to photograph Auschwitz-Birkenau, he undertook an even harder challenge. Challenge of documenting and bringing to you the images from places like Belzec, Treblinka, Sobibor, Majdanek, Zblitowska Gora and others... Nowadays for majority of people those names of villages communicate nothing and this was the reason why Paul went there. The striking thing is that they communicate nothing because the German-Nazi murderers designed those massive extermination camps to be like this. They did their best so that we would not remember.

In late 1941 the Nazi Germany decided what is the next step in their anti-Jewish policy. This was also a time when they came across the technology of mass killing in gas chambers. Technology developed due to experiments with euthanasia using carbon monoxide, experiments with gas vans in Chelmno where the exhaust fumes were directed into the back of a truck filed with people, finally experiments with cyclone B in Auschwitz. Everything to make the crime more efficient and massive but also to make the perpetrators more anonymous and less mentally burdened. The purpose was to make the crime sanitized from emotions and a factory a like process. With the massiveness of the crime there came a need to keep the major killing sites well hidden from the sight of the world's opinion and need for perfect logistics. Auschwitz-Birkenau was changed to be a destination for international transports of Jews using its concentration camp history as a cover up for the new mass extermination function. Poland in 1939 was inhabited by 3,3 millions of Jews which made it the largest Jewish community in the world of that time. In order not to block the technical capacity of gas chambers of Birkenau with Polish Jews, the German Nazis took a decision to open 4 major, extermination camps in Chelmno, Belzec, Treblinka and Sobibor.

They were to be built in scarcely populated territories, well hidden in the forests far from Western Europe, built to operate temporarily just to kill as many Jews as possible from particular well planned territory and designed to be taken apart completely after the task is accomplished.

Chelmno - 18 months of operation 150.000 people killed.

Belzec - 12 months of operation 500.000 people killed.

Sobibor - 19 months of operation 200.000 people killed

Treblinka - 12 months of operation 800.000 people killed.

The striking thing is that when you visit those places today there is not much to be seen from those camps existence. The German crime was not only about killing those people it was also about eradicating the memory about their existence and a way in which they were killed. The crime was to be perfect and the cover up took a tremendous effort. There were literally few pictures taken during those camps operation and this is making the work of Paul Brown so special today. It is thanks to his sensitivity and engagement of the Newcastel City Council that those images from the past are brought to light again. The things that are the most important on those pictures are those that we can't see at the first glance. It is important to give those images a second layer which is filled with people, corpses, screams, suffocating smoke and all those things referred often by survivors as indescribable. Small pieces of land not bigger than a soccer field were changed into ultimate accumulation of evil bringing death of 800.000 people in case of Treblinka. Evil which was developed in human brains and potentially is still there. The work of Paul Brown is important as it brings those places in front of our eyes again. They are finally brought to attention here few thousand miles away from Treblinka which was not possible in 1942. We owe this attention to the victims who were completely abandoned when the crime was committed. We owe them memory, reflection but also action. Action which would give their suffering and martyrdom a deeper sense. Action showing that their sacrifice was not in vain. Action which we owe nowadays to suffering population of Darfur, Rwanda, Iraq, Bosna and many other places which are the Treblinkas of our time. Treblinkas which are not operating in the shadow of a deep forest but killing right on our eyes.

So today Paul and his work are sending us all a very strong massage to learn from the past in order to teach and act for the better future. Thank you.